By Nick Merriman. Mian Image: Interior photograph of the Studio Gallery at The Horniman Museum and Gardens during the temporary exhibition "Lore of the Land" 2018

The introduction of a new World Gallery in June and a new community exhibition space, The Studio in October has seen The Horniman Museum and Gardens reconnect with a wider demographic and, writes Chief Executive Nick Merriman, has further confirmed the Horniman to be a space where people from all backgrounds can come together to share what it means to be human

Nick Merriman, chief executive, The Horniman Museum and Gardens21st-century museums must look back to the best of the founding impulses of Victorian liberalism; acknowledge and be honest about their problematic colonial history, and re-avow the vital importance of appealing to all and engaging their communities

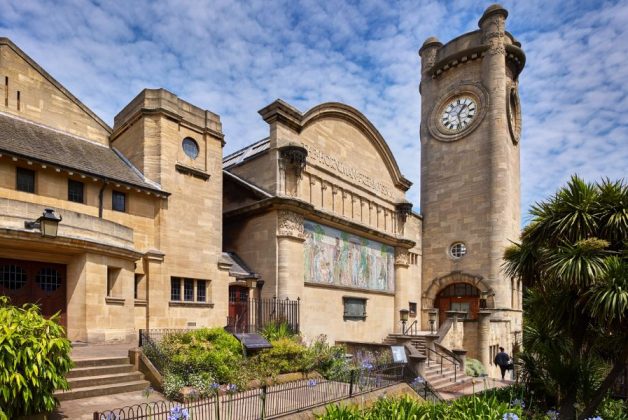

The Horniman is one of the most loved museums in the country. Since I joined as Chief Executive in May 2018, the one phrase I am greeted with most often is ‘Oh I love the Horniman!’ Founded in 1901 as a gift to ‘the people in perpetuity’ I’m sure its founder Frederick Horniman would be pleased to learn of the enduring impact of the institution he founded. Many of the people I have met reveal a pattern of visiting that goes back over generations, showing that this love and loyalty has been built up over time as a result of the close involvement and cooperation of the local community.

How do museums engender such love and loyalty from their communities and what do they have to do to ensure that it continues? This is a question that has been uppermost in my mind recently as I’ve worked closely with staff and other stakeholders to review our mission for the times we now find ourselves in. These are characterised by austerity, greater social divisions, greater diversity and rising intolerance, and set against a background of climate change and concerns about digital technologies impacting on our lives. It’s against this backdrop that we’ve strengthened our commitment to community arts programming.

Complacent

With annual visits now topping over 935,000, up from fewer than 250,000 at the turn of the millennium, our Trustees were concerned that they might be becoming complacent. As the incoming Chief Executive I had to assess whether this was a danger. What I have found is that there can be a tension between rising visitor numbers and subsequent financial sustainability, and the achievement of a social mission which, in my view, is our justification for public funding.

The Horniman’s huge success in visitor numbers masks the fact that our audience demographics are less diverse than they were 25 years ago, because the extra visitors have mostly come from the incoming middle class population that has gentrified Forest Hill and other localities. BAME audiences make up 18% of visitors compared with 40% in the London population; disabled 5% compared with 14% and NS-SEC groups 5-8 16% compared to 35% in the population.

So, we have a dilemma: should we continue as we are, with great visitor numbers and a thriving business model, but one which only attracts a certain section of the population, or should we try to widen our audiences, despite the difficulties in doing this? What would Frederick Horniman have wanted us to do?

World Gallery

Fortunately the answer was pretty obvious, and was already underway when I arrived. I was lucky to inherit a project close to fruition that exemplifies many of the qualities of a museum with a reinvigorated social purpose. The redisplay of the anthropology collections in a new World Gallery is accompanied by an introductory text which includes the lines ‘We can discover the common human virtues of love and compassion, trust and friendship, dignity and courage’. This sense of shared humanity is crucial to the success of the Gallery. Over 200 individuals from local and source communities contributed to every aspect of the gallery, from its curation to ensuring the wall texts are accessible.

For example, the Horniman’s Access Advisory Group was invited to co-curate a fascinating display case of objects linked to representations of disability and mental illness. The diverse objects chosen for the case – such as a Nigerian mother and child carving, a chameleon figurine, and a glove puppet – offered them a chance to portray themselves, as parents, artists and carers, and to counter the narrow preconceptions people often hold of disability. I am immensely proud of the project and it would not have been realised without their hard work and support.

The Studio

To extend our commitment to community collaboration, we opened The Studio in October. This is a new space that gives us the opportunity to showcase our social arts practice and where the process is as significant as the final outcome. The programme of exhibitions and events will be curated by local community members alongside artists, visitors and Horniman staff. The scale and depth of this ‘collective’ involvement is an exciting and innovative new addition to the Horniman’s ongoing work to place community engagement at the heart of the organisation. The inaugural exhibition The Lore of the Land saw contemporary artist Serena Korda work with eight local community members from a diverse range of partners including SHARP Gallery, the Arts Network and St Christopher’s Hospice, to create an immersive installation exploring humans’ relationship with the natural world.

The museum landscape we see today was essentially created in the Victorian period when a combination of taxation and philanthropy allowed them to spring up throughout the country. While many more were founded from the 1960s onwards, they were a post-war continuation of the idea that museums are contributions to the public good. They remain one of the few institutions trusted by the public, through their disinterested provision of information, their commitment to access for all, and their ability to change with the times and remain relevant.

21st-century museums must look back to the best of the founding impulses of Victorian liberalism; acknowledge and be honest about their problematic colonial history, and re-avow the vital importance of appealing to all and engaging their communities. At a time of increasing intolerance, “fake news” and a coming generation which will be financially worse off than the current one, museums provide rare spaces where people from all backgrounds can come together to share what it means to be human and to try to work out how to shape a better future for the planet we all share.